Remittances to Mexico exceed 50,000 million dollars

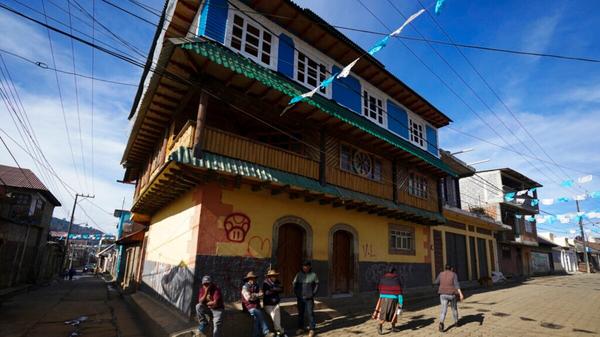

COMACHUEN, Mexico —

Remittances arriving in Mexico - money migrants send home to relatives - have skyrocketed in the past two years and are expected to reach $50 billion for the first time when 2021 figures are tallied That would surpass almost all other sources of foreign exchange in Mexico.

But as pleased as the Mexican government is with the news — authorities describe the emigrants as “heroes” — the trend raises questions: Will Mexicans always have to emigrate? And is it sustainable, or just a spike fueled in part by US government pandemic aid?

Migration

In many rural places like Comachuén, in Michoacán, all shops, businesses and families depend on remittances.

Advertisement“Without these remittances that migrants send to their families here in Comachuén, the town would have no life,” said Porfirio Gabriel, who spent nearly 13 years working on farms in the United States and now recruits and supervises people to go to the north.

During the last decade, the percentage of Mexican Gross Domestic Product corresponding to remittances has almost doubled, from 2% of GDP in 2010 to 3.8% in 2020, according to the government. In that period, the percentage of households in Mexico that received remittances went from 3.6% to 5.1%.

In the first 11 months of 2021, remittances grew by almost 27%. Mexico is already the third country in the world that receives the most remittances, only behind India and China, and Mexico accounts for around 6.1% of the world's remittances, according to a government report.

For one thing, the increase was simply a matter of necessity, due in part to the coronavirus pandemic. Mexico's GDP contracted by 8.5% in 2020, and although the economy recovered by around 4.7% in the first quarters of 2021, growth appears to have slowed and inflation has risen in the last quarter.

“When a Mexican family has a sick person or their house is damaged (...) they receive more. Because? Well, because he basically asks for help, and I think something like this has happened this year,” said Agustín Escobar, professor at the Center for Research and Higher Studies in Social Anthropology.

Ironically, some of the growth may be due to a temporary decline several years ago in the number of New Mexicans immigrating to the United States, and a decline in the relative percentage of migrants without work or residency permits.

Mexico

Escobar pointed out that this implies that migrants face less wage competition from new arrivals and people without permits.

“But in the future, how much can they keep improving? And that is an open question,” she added.

In addition, the fact that a smaller percentage of Mexican migrants work irregularly means that in 2020 more people were eligible for pandemic aid in the United States.

In a report on the Liberty Street Economics blog, the Federal Reserve Bank of New York noted that “we found that some $24 billion went to US residents born in Mexico, Central America, and the Dominican Republic between April and September” 2020 , when pandemic aid began to be delivered within the CARES law.

Although people in Comachuén say they use their money to educate their children and invest in businesses, studies show that the vast majority of remittances are used for subsistence: buying more food or medicine, or necessary appliances like refrigerators that in the long run they save families money on food expenses.

There is also a strange parallelism: the largest flows of remittances go to the Mexican states most affected by violence, such as Guanajuato, Zacatecas, Jalisco or Michoacán.

One step away from the Super Bowl, the Rams can celebrate the anniversary of the trade of Matthew Stafford

Do you have proof that the catalyst is yours? Here you must present a valid proof of ownership

The new mix of The Beatles rooftop concert arrives on platforms

Canada and the United States compete for first place in the octagonal

Escobar pointed out that emigration and crime sometimes go hand in hand. People who receive funds from abroad become targets for criminals, spreading fear and driving more people to emigrate.

“Families in Michoacán already try not to say how much they receive remittances, they try to go to a branch that is not the one next to their house, they try not to brag about this anymore, because the families that receive remittances become targets. Well, basically kidnappings to keep these people's money,” Escobar explained.

Raúl Delgado, who heads the division of development studies at the University of Zacatecas, said he sees a “vicious, perverse cycle” in the tightening of restrictions on the US border.

Restrictions make smugglers more necessary, which in turn empowers criminal gangs that harass the local population, who then leave their home community due to violence.