The pandemic pushes thousands of immigrants to return home

Ricardo Contreras was confident that if he left Honduras and moved to Spain, a peaceful and hopeful future would open up for him, his wife, but, above all, for his one-year-old daughter. Convinced, the couple sold their house, the car, took out all their savings from the bank and, in December 2019, took a plane to Barajas with the girl in their arms. They left behind reasonable jobs as telemarketers and their relatives, but also insecurity, threats from gangs and a precarious health system. The adventure, however, did not go well and the Contreras lived more than a year in precarious conditions in Alcázar de San Juan (Ciudad Real). The pandemic challenged all his aspirations and finding a job was an odyssey. When they found him, on the construction site or taking care of the elderly, they exploited them. They also felt rejected. Meanwhile, they saw their life savings disappear in a project that was going nowhere. “It was a terrible experience,” recalls Ricardo, 27 years old. In February 2021, the couple made the second most important decision of their lives: to return.

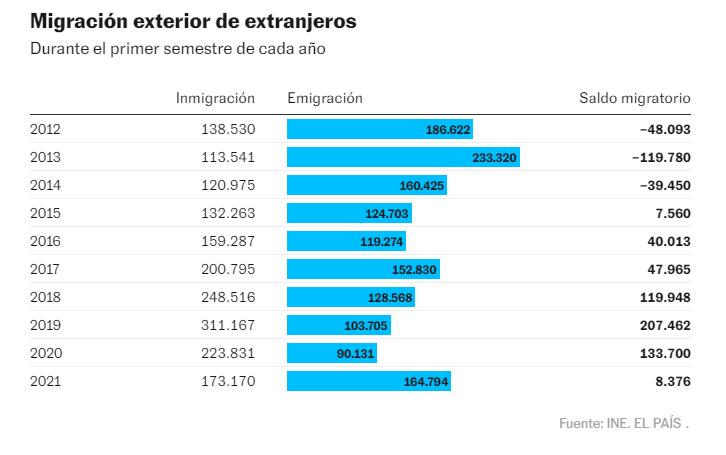

The latest population statistics from the INE reveal a significant outflow of foreigners that has not been seen since 2013, when the consequences of the economic crisis were still expelling between 300,000 and 400,000 immigrants per year. According to the latest official figures, 164,794 foreigners left Spain in the first half of 2021. Almost as many as settled, when these, for years, have usually been much higher. Most of those who left were from the European Union, especially Romanians (with 27,301 exits), closely followed by Latin Americans, among which Colombians (8,601) stand out. The number of Moroccans (17,316) is also important. There is a curious fact: more than a quarter of the immigrants who left had arrived in Spain in 2018.

There is no single reason that explains why the number of foreigners who decide to give up their immigration project has grown so much this year, but the pandemic and the economic crisis that it has brought with it have had a devastating impact, especially in seeking employment, according to organizations dedicated to facilitating the voluntary returns of immigrants to their countries of origin. In the case of Latin Americans, who in recent years have triggered asylum applications in Spain, the torrent of denials they face has also had an influence. Upon arrival, their asylum request guarantees them a temporary residence permit and they can work after six months while their file is resolved, but when their request is rejected they remain in an irregular situation overnight.

The Contreras family does not lavish much on their social networks, but in all their photos in Spain they seem happy. It was his facade. When they arrived, he worked in construction for a couple of weeks and it took three months for them to pay him less than they owed. He later found a job in the kitchen of a restaurant, but then the pandemic hit, the place closed and he couldn't get any more work. His wife began taking care of an old woman from eight in the morning to eight at night. She “They paid her 400 euros. She basically earned her rent. She didn't give us ”, recalls her husband from Honduras. The woman left that job because she got a better one: cleaning a house for 700 euros. Savings were melting away in order not to depend on charity. “Our life was searching and searching and handing out résumés all over the place,” she explains.

What affects the most is what happens closest. To not miss anything, subscribe.Subscribe

The family also did not feel well treated. "Of course there were good people who helped us, but on more than one occasion, in the park, on the street or in the supermarket, they looked at us badly or told us to go to our country," laments Ricardo. “After trying and trying, giving our best, being kind and everything, we couldn't take it anymore. We did not want to live as a gift, we did not like to ask”. The Contreras left without even knowing if their asylum application would be approved. "It was difficult, but it was the best decision, now we have found new opportunities here."

I liked a @YouTube video https://t.co/6UYEhFAeA1 How to Remove virus manually Using CMD 2018 windows 10,8, 7

— Fauziah Hasan Thu Apr 12 00:02:39 +0000 2018

The NGO Red Acoge is one of the 11 entities that receive public subsidies to help immigrants return to their country. Most foreigners leave on their own, but those who knock on the doors of these organizations are those who can't take it anymore, those who can't even afford a return ticket. Vega Velasco, coordinator of the voluntary return project of this NGO, traces the profile of the last immigrants they have attended. “We are identifying cases of increasingly vulnerable people, not only because they do not have the means to pay for their basic needs and depend on aid, but also because they are people with serious illnesses, homeless or single women with children whose situation is It has been aggravated by the pandemic.” According to Velasco, there are more and more people from Central America, a very large profile among asylum seekers. “There have been many denied applications that have left thousands of people without documentation,” she explains. "They came with very high expectations and when they arrived here they have seen how difficult it is to find a job or a home without papers."

Jean Carlos Romero, 27, was unfolding in Nicaragua, to finish his Economics degree at night and fulfill his day at a customs agency during the day. He was running 2018 and the political and economic situation in his country was getting worse by long steps. "I always saw emigrating to Spain as a golden opportunity to study and work," he says by video call. The young man landed in an inn in Bilbao on October 22, 2018 with $1,000 in his pocket and "too much innocence." He lived most of the time in A Coruña, he was excited and it shocked him a lot to be able to walk down the street at night without fear of being mugged, but problems soon began.

The young man wanted to resume his studies, but he did not have the money it cost to do the paperwork in his country or pay the tuition here. He also had little luck with work. “I got some small jobs painting, cleaning fish in the harbor and in a restaurant,” he recalls. He earned between six and 7.5 euros an hour. And then the virus came and he had to lock himself up. “With the pandemic I felt much worse, because before, at least, I could look for a job. It was very frustrating to spend so much time doing nothing,” he recalls.

Once the confinement was over, Romero did not find a job again. He had municipal help to pay for a room but it ran out and in October 2020 he was denied asylum. That and seeing how his classmates posted their photos of graduation parties finished him off. It took him a few days to make the decision, although he had to ask Red Acoge for help to pay for his return. "It was very hard to become dependent on people," he laments. The young man returned to his grandmother's house in Nicaragua on January 25 and has already resumed his studies and a new job. He is happy, although uneasy with the uncertainty that exists in his country. His experience, he consoles himself, served him, at least, as an apprenticeship. "I got excited about an idea and then I realized that it was very difficult," he laments. He does not rule out looking for luck outside his country again, but not like this. And not in Spain. "My biggest mistake was not having informed myself better."